Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics

Up |

|

The world of the periodical essay: Social networks and discourse communities in eighteenth-century London Susan Fitzmaurice (contact) (University

of Sheffield) Received: July 2006, published March 2007 (HSL/SHL 7)

1. Introduction The backdrop for the study reported in this paper is a long-term interest in the role of social ties and community in influencing the social behaviour and practices represented by language use. The database used for this is a network of eighteenth-century men and women in London between approximately 1670 and 1760, centred on Joseph Addison (1672–1719) and represented by an electronic corpus of early eighteenth-century texts written by members of this network (Network of Eighteenth-century English Texts). Accordingly, my exploration of language use and social influence has been grounded in social network analysis, which affords an analysis of the ways in which the associations that are formed by actors, such as coalitions, support the pursuit of particular goals and in particular projects. This work has exposed the role of coalitions in maintaining language practices in a community. In particular, the coalitions formed around Addison’s and Steele’s Spectator project between 1710 and 1714 was instrumental in providing pressure for actors to adhere to a set of norms associated with the powerful members of the coalition. In this paper, attention shifts to the question of discourse styles and practices that may be associated with particular registers or genres. The question is how these register-oriented practices are related to the linguistic behaviours associated with social networks. For example, it is interesting to ask whether the practices that we observe to be shared by members of the network who were also involved in the Spectator coalition are characteristic of the wider community of periodical writers. In this instance, it would be interesting to examine the extent to which people outside the social network, like Daniel Defoe, nevertheless appear to subscribe to the practices and norms adhered to by periodical essayists in general, including those of the Spectator writers. I submit that social networks provide the scaffolding for the study of discourse communities in a particular milieu such as early eighteenth-century London. The primary data is provided by the essays sub-corpus in the Network of Eighteenth-century English Texts corpus (NEET).[1] Of the literary community in early eighteenth-century London, Dobree and Davis (1969:220) observe that “after the restoration, with the rapid development of a well-organized literary community in London, the author-reader relationship was correspondingly transformed, and the writer was able to direct his observations to a body of readers whom he could easily visualize, and with whom he might almost be said to converse”. They go on to comment that despite this new literary and literate world, “it was some time before these new conditions led to any considerable growth in essay writing”. However, they do suggest that the last decades of the seventeenth century set the conditions in which writers begin to conceive the particularly interactive – what I have called the intersubjective – style of appeal and address to the reader that typifies the essay as exemplified by the Spectator and Tatler. The periodical essay is recognized, to all intents and purposes, as a new genre in the early eighteenth century. It is not entirely novel of course, but has its antecedents in other forms and practices (which I won’t rehearse here). I am interested in examining the extent to which members of the social network participate in the practices of a wider discourse community of essay writers in the period. In order to compare the roles of social networks and discourse communities in shaping language use, I examine the meaning and use of a set of linguistic features in the letters and essays of the men and women in the NEET corpus. This study will allow us to ascertain the extent to which writers adhere to styles and conventions that may be established with the practice of writing a particular genre or register (however implicitly). The research questions for the present study are informed by a study of the emergence of intersubjective comment clauses and their development as discourse markers (you say, you know, see) in letters and prose drama using the ARCHER corpus (Fitzmaurice 2004). It also builds on my study of the grammar of stance in the NEET letters subcorpus, specifically of modal expressions, epistemic and attitudinal stance verbs – hope, think, know, wish, desire – with complement clauses (Fitzmaurice 2003). In this paper, I expand on various aspects of these findings, using the NEET corpus to explore the use of stance verbs with both first and second person subjects as comment clauses in essays. As stance expressions become routinized in discourse, it would seem reasonable to expect them to diffuse into different registers. Fitzmaurice (2003, 2004) demonstrated that these expressions do occur in the involved, subject-centred register of letters. Their occurrence in eighteenth-century essays might be taken to indicate the extent to which the essay of the period might occupy a stylistic space that is not as distant from letters as that occupied by the essay’s present-day counterpart, academic discourse. The following questions thus guide the study:

The last question is the most tentative and exploratory, and perhaps can be only partially addressed by the work reported in this paper because linguistic practices comprise a suite of choices that together distinguish the genre of the discourse community. In the sections that follow I first discuss social networks and the ways in which the periodical writers in early eighteenth-century London might be regarded as constituting a discourse community. I then outline the research procedure followed, and then present and discuss the findings and offer some directions for further investigation. 2. Social networks and discourse communitiesSocial networks analysis (SNA) provides the basis for examining the ways in which actors cooperate in specific projects in order to achieve certain goals. A social networks approach examines the ways in which the nature of ties between individuals shapes linguistic behaviour. Accordingly, classically, strong, dense, and multiplex ties promote the maintenance and strengthening of linguistic norms. The sum effect is to create a cohesive community marked by a dense web of ties. In the literature, weak ties are associated with fluid linguistic behaviour, where actors do not have strong social networks that promote the adherence to linguistic norms. The notion of “network” adopted here is a technical one, developed in the fields of anthropology, social psychology, sociology, epidemiology, business studies, economics, and recently, in sociolinguistics, to describe the relationship between individuals and the social structures which they construct and inhabit (Boissevain 1974; Wasserman & Galaskiewicz 1994; Milroy 1987, Milroy & Milroy 1985, Milroy 1992). A “network” refers to a group of individuals whose connections to one another are made up by social ties of varying strengths, types and lengths. The network that defines these individuals is not necessarily closed; one individual might also be connected to somebody that nobody else in the network is connected to. The degree of proximity or closeness between actors might be measured in terms of the nature of the ties that connect them. The parameters on which strength of ties are calculated are:

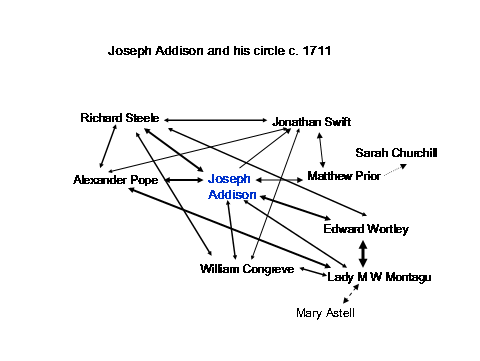

The social networks formed by and around Joseph Addison provide the basic design and rationale for the construction of the NEET corpus. Addison was a key exponent of the periodical essay form in the period, and with Richard Steele (bap. 1672, d. 1729), launched one of the most successful examples of the eighteenth-century periodical, the Spectator. Previous work has examined in detail the impact of the Spectator coalition on the language and culture of the period (Fitzmaurice 2000a). The men behind The Spectator formed a group which developed identifiably political and literary ties to achieve particular goals, which include personal success and fame. Addison’s own pursuit of the protection and sponsorship of powerful men like Halifax and Somers demonstrates quite clearly the usefulness of social networking, as does Pope’s pursuit of Addison himself in 1710. The coalition was also allied with a particular political grouping, the Whig parliamentarians and government managers, who saw themselves as forward-looking and progressive in comparison with the Tories. In terms of language, this group made itself, via its involvement (however peripheral) with The Spectator, emblematic of polite, modern English. Addison’s own network consists primarily of people who are old friends, colleagues and enemies, who share correspondences, political convictions and loyalties, who collaborate in publishing projects and who contribute to the same periodicals. Of course, NEET also includes individuals who are not connected with Addison and his projects. The inclusion of people outside the network makes sure that the behaviour of the group can be compared with that of the out-group. Despite the fact that NEET’s design is principally informed by the social networks formed by Addison, the corpus also captures important aspects of a particular discourse community of the time. Many of the participants in the Spectator coalition collaborated on other periodical projects. In addition to working together on the Spectator project, Steele, Addison and Jonathan Swift (1667–1745) had earlier cooperated in developing the Tatler. Addison was highly successful in recruiting young writers to the Spectator group (and to the Whig cause), adding Alexander Pope (1688–1744) , Eustace Budgell (1686–1737), Ambrose Philips (bap. 1674, d. 1749), Thomas Tickell (1685–1740), and John Hughes (1678?–1720) to the coalition. Steele and Addison also sought contributions from Pope for their next venture, The Guardian, yet Addison worked more or less solo on The Freeholder. A year after the closure of the Spectator, Steele and Swift conducted a public and vituperative row over their respective political affinities. Their quarrel was occasioned by an unflattering portrait of the Duke of Marlborough in the pages of the Tory Examiner, which Steele, in the Whig Guardian, attributed to Swift.[3] The Examiner was launched in the summer of 1710, and drew the participation of prominent Tory politicians like Henry St. John (1678–1751), who provided much of the paper’s political impetus, Francis Atterbury (1663–1732), as well as civil servants like Matthew Prior (1664–1721). Swift’s contributions to The Examiner comprise thirty-three essays written from a Tory point of view “to assert the principles, and justify the proceedings of the new ministers”. The paper was published on Thursdays from 2 November 1710 (no. 14) to 14 June 1711 (no. 46, jointly written with Delariviere Manley, c.1670–1724, the subsequent editor). Swift's essays were each answered in The Medley on the following Monday by Addison's friend, the Whig MP Arthur Mainwaring (1668–1712). Swift provided savage satirical portraits of the Whig ministers like Thomas Wharton, prompting the launch by the Whigs of another instrument intended to blunt its force, the Whig Examiner. Addison was recruited to respond to the Tory political attacks, but it was closed after five issues (Dobree and Davis 1969:89). Although the Spectator and Tatler continued to be regarded as the most influential periodicals of the time, there was another more overtly political and much longer lived periodical that commented on the party wars and appealed to the man in the street. This was Daniel Defoe’s A Review of the State of the British Nation (1704–1713). In addition to these papers, there were other party-sponsored periodicals, including the Mercator which was designed to support Robert Harley against the Wig British Merchant (Dobree and Davis 1969:96), as well as Steele’s The Englishman (July–November, 1715).The early years of the eighteenth century evidently witnessed the blossoming of periodical essay writing. Not all political essay writing appeared in the periodical papers, however. All of the people I’ve mentioned wrote essays for pamphlet publication as well as for periodical publication. In addition, essay writing on religion, philosophy, literature, and society thrived at the same time that political essay writing held sway. The essay seemed to be the big new thing in the literary community, building on the foundations set by Dryden’s literary criticism, as exemplified in his Essay on Dramatick Poesie (1684). In form the eighteenth-century essay occupies a stylistic space between the letter and the dialogue. Essay authors tend to adopt a persona, exemplified most vividly by the Tatler’s Isaac Bickerstaff. They also typically appeal to the reader directly in adopting conventions that seem to be more characteristic of the letter or of the newspaper feature than of the essay now conceived. To the extent that there is a recognizable set of practices associated with essay writing and production at the time, I will invoke the idea of the discourse community to describe the behaviour that the essay writers of the period observe. The discourse community is a concept developed in applied linguistics and rhetoric research to capture the shared conventions and practices observed by people in a shared field or occupation (e.g. Swales 1988, Johns & Swales 2002). Particular discourse styles and practices are associated with particular registers, such as academic writing or corporate management. These practices and conventions may not necessarily be explicitly prescribed but they must be sufficiently valued to be upheld as norms of the domain, and targets for participants new to the field. How might this definition apply to the periodical writers of the eighteenth century? Periodical writing requires the production of a commodity – the periodical paper – that meets the demands of a publication produced and distributed at regular intervals for a readership interested in current affairs (however this is defined). The practices that would seem to cast periodical writers as a discourse community include their adherence to a set of genre or register conventions, recognition of practices which members would easily identify, and adherence to a rhetoric and style designed for periodical publication on the one hand and for a periodical audience on the other. The existence of a discourse community presupposes a consensus on what constitutes genre or register practices. The techniques and data afforded by a corpus linguistic approach to the study of eighteenth-century texts provides the opportunity to examine the extent to which register or genre appear to shape writers’ linguistic choices. Now we ought to make a distinction between writers who regularly produce work for periodicals –publications produced regularly in order to be delivered at a fixed time – and those writers who were not constrained by having to write on a prescribed topic to tight timelines. Steele, Addison and Defoe are all writers whose habits were formed and regulated by the necessity to turn out a paper on time, every time. Although Swift, Pope, Prior and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (bap. 1689–1762), were asked to contribute to periodical papers, and though Swift and Montagu, for a short period were each responsible for the production of a periodical, their work was not confined to the medium of the periodical. They also all published essays as single one-off pamphlets. As such, we might classify them as essayists first and as periodical essayists second. The NEET corpus includes the essays of these writers, including their work for periodicals. However, NEET also comprises essays of people who were not part of London’s popular periodical writers but who nevertheless produced essays for publication, sometimes a long time after their completion. Mary Astell (1666–1731, though known to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (bap. 1689, d. 1762), was not connected with Addison and his circle. However, from 1696 with her publication of the controversial essay, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies for the Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest, she was established as a serious, not to say notorious, essayist. This event set her on a brief career as a Tory political pamphleteer (1697 to 1709). A serious theologian, Astell began exchanging letters with the Cambridge Platonist John Norris (1657–1712), rector of Bremerton, who published their correspondence in 1695 under the title Letters Concerning the Love of God. Susanna Wesley (1669–1742) is altogether different from the other writers of essays collected in NEET. Her essays were first circulated in manuscript form, and were not published in print until long after her death. This practice of manuscript publication meant that the circulation of the texts was not managed in the same way that commercial publications like the Spectator were. Additionally, unlike the Spectator which was easily available to anybody from commercial outlets like print-shops and coffee houses, Wesley’s essays were transmitted from individual reader to reader only by association. William Congreve (1670–1729) and John Dryden (1631–1700) are essay writers, though their essays appear in different domains from the others. Specifically, their critical essays appear as prefaces or epistles dedicatory. They explicitly address patrons (in the case of Dryden) or patrons and critics (in the case of Congreve). Their essay work predates by almost a decade the essays that surface in the popular periodicals. Congreve’s Amendments of Mr. Collier's False & Imperfect Citations, etc. (1695), shares with Astell’s Serious Proposal the notoriety that attends controversy. Although John Dryden was dead by 1700, his work is also collected in NEET because he was so influential on the literary careers of Addison and his cohort. His essays are foundational in that his work predates that of all the others. Sutherland remarks as follows on his work: The easy and familiar tone of Dryden in the various prefaces that he wrote for his plays was partly due to many of those pieces being addressed to individuals in the form of dedications, but also to his awareness of the fact that most of his readers had already seen his plays, and that to this an acquaintanceship already existed. Long before he had reached old age, however, Dryden’s conversational manner had become habitual with him, and in this, as in so many other directions, his influence on the age must have been considerable (Sutherland 1969:220). As we shall see, it is possible that it was Dryden’s essay style that provided the standard for the intersubjective style that the periodical writers seek. Let me try to distinguish between the social network that has as its centre one of the founders of the Spectator, Joseph Addison, and the more elastic alliance represented by a discourse community of essay writers. To do so, I present below two diagrammatic representations (Figure 1). The first is Addison’s social network around about 1711. Note that I have included the names of individuals who have very indirect or tenuous connections with members of Addison’s network (Mary Astell, via Lady Mary Wortley Montagu; Sarah Churchill 1660–1744, via Matthew Prior).

In contrast is the representation of London’s essay writers (Figure 2). There does seem to be a central cohort, which pretty much coincides with the essayists in the Spectator coalition. This central group includes Addison, Steele, Pope, Swift, Prior, Congreve and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. The others have nothing to do with the Spectator, but arguably are part of the discourse community by virtue of their participation in essay writing and publication. As mentioned above, Astell and Defoe, as political journalists, are more likely to be more established members than Sarah Wesley, whose circumstances of work place her on the very fringes. Note that Sarah Churchill, as an aristocratic memoirist far removed from the world of publication for profit, is absent from this picture. Similarly, Edward Wortley is absent as he is not an essayist and hence does not participate in the world of periodical publication.

2.1. Discourse communities and intersubjectivity In the light of the discussion of discourse communities and social networks, I offer two hypotheses in this study. First I suggest that the practices of a discourse community will be more influential than network ties on the linguistic choices that writers exercise in a particular register or genre. For example, Defoe’s essay style will be more compatible with that of the other periodical writers than not, despite his exclusion from their social networks. In other words, the discourse community to which the essay writers belong (whether they know it or not) will provide a more compelling model and set of practices than social ties. Further, I expect that writers who are not part of the discourse community will not exhibit the same linguistic choices or behaviour in their production of the same register or genre. Secondly, I suggest that the more established the discourse community, the more consistent the practices across its exemplars. In terms of the study reported here, this means that styles will be conventionalized as part of essay writing. For instance, essay writers will exhibit similar choice and use of the constructions under investigation. Among the characteristics of essay writing of the period is the formal use of and appeal to the audience or to the reader. In formal terms, the appeal provides the framework of the essay, so it is not unusual for the arguments put forth in an essay of the period to have an addressee. Congreve’s essays and Dryden’s essays clearly have the framework of an address or a letter. Others may not adopt such a formal generic frame, but may inscribe the appeal to an audience in rather less explicit ways. For example, the writer may seek to engage the audience by involving it directly in argument and debate by constructing sympathetic or contrasting views or positions and attributing them to the audience or reader. Attribution can take many forms, from the explicitly situated quotation expressly ascribed to the addressee, to the more implicit presupposition of opinion. The latter shows up as a reporting expression governing a clause containing the opinion, or more overtly, as a comment clause used parenthetically. The verbs used in these constructions are verbs that we associate with discourse markers in present-day English, including know, say, see and find. Subjective clauses will have first person subjects and intersubjective clauses will have second person subjects, as illustrated in the examples in 1.

For the purposes of this study then, intersubjectivity has to do with the representation of speaker stance as addressee stance, and thus involves the transformation of propositional meaning from new information to presuppositional meaning. Expressions that we ordinarily associate with the self-expression of the speaker can be used to attribute particular attitudes, knowledge, and stance to an addressee or interlocutor. For example, though infinitive and that-complement clauses governed by mental verbs, comment clauses, and modal verbs are usually associated with the speaker’s rhetorical self-positioning, these same resources may be marshaled for the speaker’s rhetorical construction of the interlocutor’s perspective or attitude. So, there is a difference between using an explicitly subjective epistemic stance marker such as a complement clause governed by an epistemic verb like know and the first person (as in 1a above), and what I suggest is an intersubjective stance marker such as a complement clause governed by know with a second person subject, as illustrated in example (4b) above. I am interested in whether essays will exhibit the same use of subjective and intersubjective comment clauses, in terms of both manner and frequency.

3. Procedure 3.1. Corpus I used the letters and essays subcorpora of the NEET corpus in order to compare the extent to which genre or register considerations override idiolectal characteristics. The details of the subcorpora are summarized in Table 1:

Table 1. Numbers of words in individual subcorpora (letters and essays). Monoconc, a commercial concordancing package, was used to conduct a search of the letters and essays subcorpora for lexical expressions with know, see, find, suppose and imagine. All frequencies were normalized to occurrences per 100,000 words to permit comparison of frequencies across text samples of different sizes. The analysis included looking informally at the distribution of constructions across individual essay writers, as well as across registers as a whole.

3.2. Linguistic features The following specific constructions were investigated:

It is important to note that I did not exclude from consideration expressions that included modals or modifiers in the stance verb phrases or comment clauses. Accordingly, included were expressions such as those illustrated in (5):

Note that the modification includes negation – quite common with know in collocation with the first person.

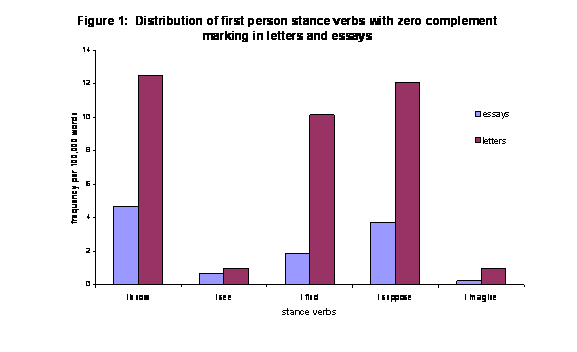

4. Results and discussion Figure 1 summarizes the relative distribution of first person stance verbs (know, see, say) in letters and in essays by the same actors. Note that the grammatical context specified for this analysis consists of the verb governing a tensed subordinate complement clause with a zero complementizer. Figure 3. Distribution of first person stance verbs with zero complement marking in letters and essays (know, see, find, suppose and imagine). The figures are quite small overall – unsurprisingly for lexical strings– but the difference between the frequencies for each register is striking. First person verb phrases with know occur nearly three times more often in letters than in essays, first person verb phrases with find occur five times more often in letters than in essays, and first person verb phrases with suppose occur about four times more often in letters than in essays. However, more striking in light of our discussion about the stylistic positioning of essays in the period as involved and engaged with the reader is the fact that these stance features occur in essays at all. Their presence would seem to suggest that the essay in the period is participating in the work of expressing opinion, as illustrated in the examples from Defoe’s Review with know and find in (6) below.

Table 2: Frequencies of first person subject stance verbs (per 100,000 words)

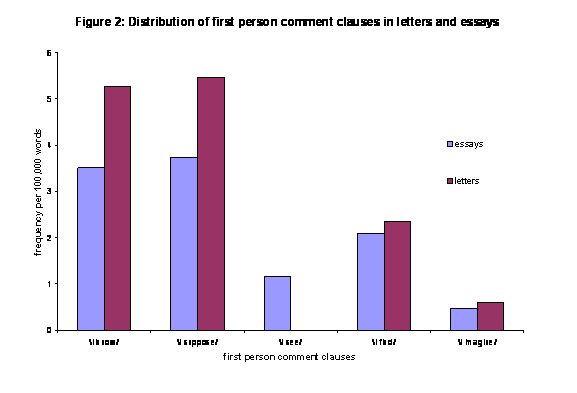

The second question for investigation concerned the use of epistemic verbs like suppose, imagine and find in comment clauses with first person subjects, and with second person subjects. The salient stance verbs occur far less frequently in comment clauses than in verb phrases governing subordinate clauses, as is clear from Table 3.

Table 3: Frequencies of first person comment clauses (per 100,000 words). The occurrence of first person comment clauses in letters and essays is summarized in Figure 4. Figure 4. Distribution of first person comment clauses in letters and essays. Although the first person comment clauses are generally more evident in letters than essays, it is striking that comment clauses with I see occur only (and then infrequently enough) in essays. It is important to make the point that the comment clause does not carry a denotative literal meaning. Instead, “I see” might be construed as “I surmise” or “I understand” in these contexts. (The most common occurrence of “I see” in both registers is unsurprisingly as a sense verb with a simple noun phrase direct object.) In addition, the stance verbs find and imagine occur in first person comment clauses infrequently in both registers, but just slightly less often in essays than in letters. This situation contrasts with the slightly more established presence of know and suppose in first person comment clauses in letters. The examples in (7) illustrate the range of uses to which the stance verbs are put in first person comment clauses, again, in the essays subcorpus. In each case, the effect of the first person comment clause is to express the opinion of the speaker – and thus stamp a perspective or interested position on the presentation of the information conveyed in the essay. Three of the examples, (7a), (7c) and (7d), are from periodical essays. In the first case, the persona represented is not the writer’s, but that of the paper’s subject, the abused wife. Similarly, in (7c), Steele represents the Whig opinion of one of the Spectator’s characters, Sir Andrew Freeport, against the Tory Sir Roger de Coverley. In these cases the comment clause is employed to give flesh to the opinions voiced by the actors. In the case of (7d), the persona is an Italian impresario who proposes to export to England, Italian opera singers and cooks to feed the desires of the British people. This essay is presented as a letter to the editor of the journal; it is evident that in keeping with the periodical community’s practice of constructing letters for the body of the paper, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu ensures that her paper addresses the topic of imported culture by relying on the same.

Examples (7b) and (7d) do not invest the speaker with a persona separate from that represented by the author. It is worth turning to the analysis of the extent to which comment clauses with second person subjects occur in the two registers to ascertain the role of the audience in the two. Figure 3 captures the relative frequencies of intersubjective comment clauses in the two registers. Figure 5. Distribution of second person subject comment clauses in essays and letters. The distribution of second person comment clauses seems to follow the pattern observed for first person subject comment clauses in the two registers. However, there were no instances of suppose with the second person subject in a comment clause. Indeed, there were no instances of the second person subject with suppose governing a subordinate clause with a zero complementizer in essays, and only negligibly so (0.2 per 100,000 words) in this construction in letters. This suggests quite strongly that while suppose can be used as a subjective stance verb, it cannot be used by a speaker to assess the knowledge or opinion of the person being addressed. However, suppose can be recruited in collocation with the impersonal third person pronoun some with as and the hedging modal may, as in the following example taken from Addison’s Freeholder essays:

Addison’s expression, favouring neither speaker nor addressee, has the effect of hedging. However, the inclusion of the epistemic verb in a comment clause invites the inference that it is being used to draw attention to the negative intentions of his subject, namely, “[t]hese Potentates”. Swift uses the verb as an imperative with a following comment phrase, for Argument sake, and a complement clause marked by that as in (8b).

Swift’s use is more explicitly intersubjective as it implies the active intellectual engagement of the reader in the arguments put forth in the essay. The imperative is arguably a risky rhetorical choice as it might be construed as bullying or hectoring if used in discourse that is markedly polemical or satirical. Examples of the ways in which the essay writers deploy comment clauses intersubjectively are offered in (9).

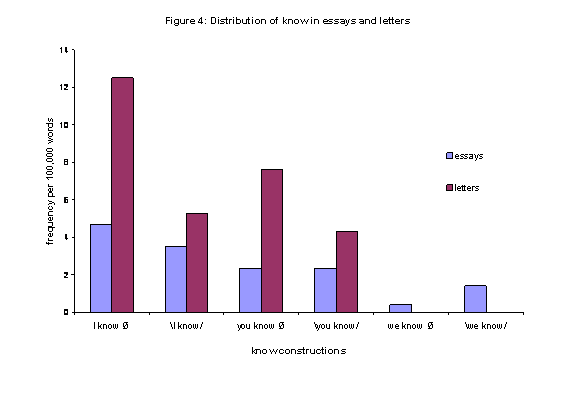

Although Pope’s Letter, written in 1733, was designed to respond immediately to a verse attack against him by John, Lord Hervey, it was published only in 1751 (Cowler 1986:433). Pope’s more public and lasting retort was the Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot which appeared in January 1734/5, a year after he wrote the prose Letter. Cowler characterizes the Letter as a “straightforward, restrained, personal response” which “instead of transcending the personal and temporal, bears hard upon it” (1986:435). In the extract quoted in (9a), Pope explicitly yet ironically acknowledges the possibility that his noble addressee might interpret his comments as hostile, which of course they are. The effect is withering. Defoe’s use of you know in (9b) assumes a confiding, gently conspiratorial not to say patronizing tone as he constructs the habits and interests of a government made up of women. Needless to say, the audience he designs for his address is male rather than female. In (9c) John Dryden exhibits the language that prompted Sutherland to remark on his conversational style as “I habit”. He constructs a dialogue between his reader and himself, attributing attentiveness and understanding (you see) and opinion (you say) in an unfolding argument about writing in verse. Interestingly, he adopts the possessive pronoun your to modify “‘Rhyme”, but here it serves a familiarizing function with generic reference rather than specifically attributing possession (or a position) to his reader. The effect of the use of the second person comment clauses is to establish an interactive tone, drawing focus away from the speaker-subject and his stance. Let us now turn to the closer examination of a verb with first and second person subjects in the essays in order to discover whether their functions distinguish them as stylistic options that serve the essay genre. In other words, is it reasonable on the basis of these features to suggest their role in contributing to a nascent essay style that comes to be typical of the periodical essay? I’ll examine the distribution and use of know in essays as compared with its occurrence in letters in an exploratory gesture in this paper. Figure 6. Distribution of know in essays and letters. Figure 6 captures the distribution of know with first person singular and plural as well as second person in stance verb phrases with zero complementizers and in comment clauses. The reason for adding to the inventory of constructions know with first person plural subject we was to find out whether the reader’s participation in the discourse of the essay shows up in other ways, and ways in which it does not occur in letters.

Table 4: Frequencies of know (per 100,000 words). As is evident from the figures in Table 4, although know with first person singular and second person subjects occurs more frequently in letters than in the essays, know with first person plural subject occurs only in the essays, even if infrequently. Let us examine the ways in which we know is used in the essays, as illustrated in (10) below:

In the examples in (10), taken from Swift’s essays, Conduct of the Allies and Abolishing Christianity, we see the phrase used as a stance verb phrase (a, b), and as a comment clause (c, d). The stance phrase seems to be deployed in order to situate the dominant position of the interest group for which the writer speaks. Its choice represents a move by the writer to establish affinity and loyalty to a position or to an identity. In the case of (10a), we and us have the same referent, namely, the English people. In (10b), Swift distinguishes the singular from the plural; he uses the singular I to mark his conscious choice of an opinion on the basis of popular intelligence. The effect is to underline the unity of the writer’s position with that of the constituency of protestants for which he speaks and whom he addresses. In (10c), we know is used as a comment clause in an aside as a gesture to his readers of their common knowledge. Example (10d) represents an emerging use in a comment clause, for aught we know, an idiomatic expression also used frequently by Defoe and Dryden with the first person to inject an intersubjective comment into a claim or statement. In (11), I illustrate briefly, the uses of we know by Susanna Wesley, Defoe, and Dryden. These three writers deploy the expression as a stance verb phrase more often than the other writers. This fact requires further investigation in order to discover whether their preference for the expression is a function of the subject matter or whether it is a feature of their essay writing more generally. Susanna Wesley conjoins know with feel, and preposes the object pronoun it to allow a cataphoric construction in which the object is elaborated in a formal fashion.[4]

Defoe deploys the stance verb phrase in the representation of a statement by Queen Anne about the exiled deposed king in France. And in Dryden’s Essay, he allies himself with the audience at a play, sharing the knowledge of being willingly deceived by the suspense of reality in drama. In these examples in (11), we know is used fairly literally to refer to a general belief or intelligence, which the writer shares about a state of affairs. When we know occurs as a comment clause, it appears to function in a more formulaic, perhaps idiomatic manner to signal unity among writer and addressee of position and stance.

5. Concluding observations There is not space or time to elaborate these results further here. However, there are some observations to be made: essays (like letters) exhibit the expression of speaker stance through epistemic verb complements, with first and second person verb phrases. Letters exhibit the more frequent use of comment clauses than essays do, and the letters exhibit more frequent use of both subjective and intersubjective comment clauses than essays. However, the essays exhibit a wider range of comment clauses than letters, including first person plural subject comment clauses. Is it fair to conjecture that comment clauses with second and first – particularly first person plural – subjects are features that typify the early eighteenth-century essay? It is clearly too soon to say, although the fact that the essays appear to adopt these expressions prompts the wider and more fine-grained analysis of other intersubjective features that might be regarded as marking the essay’s situation as a genre that leans towards the involved, highly interactive personal letter in its form and in its appeal to its readership. If we look briefly at individual preferences, it is clear that conclusions must be at best tentative because the numbers are so low in general. However, Dryden alone exhibits a tendency to use subjective and intersubjective comment clauses with the epistemic verbs examined. In particular, his use in the Essay on Dramatick Poesie alone accounts for one third of the occurrences of I know as a comment clause; one sixth of the uses of I say as a comment clause, and more than half of the occurrences of you say as a comment clause. This is particularly striking because Dryden’s essay predates the writing of the others by at least a decade if not longer. Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift, Richard Steele, Alexander Pope and William Congreve adopt a practice that echoes Dryden’s, but theirs is much more tentative and sporadic in terms of frequency and distribution across their writing. It is worth noting that these men are in the thick of periodical publication in London, and it is conceivable that their practices begin to mark the community norms associated with the periodical essay in particular. Curiously, Joseph Addison does not participate in the practice to any discernible extent, and it will be necessary to look more closely at his essays, together with those of the group just mentioned, across the different periodicals between 1709 and 1715 to track the emergence of a set of practices that could confidently be argued to characterize the periodical essay. The women essay writers, Susannah Wesley, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Mary Astell require further scrutiny to determine properly whether they adhere to particular patterns of use, whether shared with their male counterparts or not. There is much to be done. However, what is striking is that there does appear to be some merit in looking at patterns of language choice that might be associated with a discourse community involved in the production of essays, and in particular periodical essays. The fact that the writers of these periodicals appear to share preferences with respect to stance expressions and comment clauses suggests that the production of the genre is the mechanism that overrides the role of social ties with respect to language choice. This is supported by the observation that Defoe and Steele behave similarly despite the absence of social ties, and that Dryden and Defoe behave similarly despite the absence of a social tie, and that Dryden and Swift behave similarly despite the absence of a social tie. Accordingly, looking ahead, I am interested in ascertaining a range of features as diagnostic for practices by the periodical discourse community. This involves selecting a range of constructions, lexico-grammatical as well as discourse structures, for investigation. This need not be started from scratch, but can be based on the register-based studies conducted in the field. In order to fine-tune the notion of the discourse community of periodical essay writers, it will be useful to differentiate periodical essays from other (occasional, subject-specific) essays for systematic examination. The analysis must also include a study of dates of publication as well as publication history of the periodicals and manner of transmission in order to establish the emergence of discourse practices that mark this community, and the ways in which social relationships interact with discourse community to shape language use in the period.

References: Boissevain, Jeremy. 1974. Friends of Friends: Networks, Manipulators and Coalitions. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Carley, K.M., & D. Krackhardt, 1996. “Cognitive inconsistencies and non-symmetrical friendship”, Social Networks 18, 1-27. Cowler, R. (ed.). 1986. The Prose Works of Alexander Pope. Vol II: The Major Works, 1725-1744. London: Basil Blackwell. Dobree, B. and N. Davis, 1959, repr. 1976. English Literature of the Early Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Fitzmaurice, S. 2004a. “Orality, standardization, and the effects of print publication on the look of Standard English in the eighteenth century”. In: Dossena, Marina and Lass, Roger (eds.), Methods and Data in English Historical Dialectology. Bern: Peter Lang. 2004: 351-383. Fitzmaurice, S. 2004b. “Subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and the historical construction of interlocutor stance: from stance markers to discourse markers”. Discourse Studies 6/2. 427-448. Fitzmaurice, S. 2003. “The Grammar of stance in early eighteenth-century English epistolary language”. In: Charles Meyer and Pepi Leistyna (eds.), Corpus Analysis: Language Structure and Language Use. Amsterdam, Rodopi. 2003. 107-131. Fitzmaurice, S. 2000a. “Coalitions and the investigation of social influence in linguistic history”. EJES (European Journal of English Studies) 4/3. 265-276. Fitzmaurice, S. 2000b. “The Spectator, the politics of social networks, and language standardisation in eighteenth-century England”. In: Laura Wright (ed.), The Development of Standard English, 1300-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 195-218. Hyland, K. 1999. Disciplinary Discourses: Social Interactions in Academic Writing. Harlow, England: Longman/Pearson. Johns, A.M. and J. M. Swales. 2002. “Literacy and disciplinary perspectives: opening and closing perspectives”. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 1. 13-28. Johns, A.M. 1997. Text, Role, and Context: Developing Academic Literacies. New York: Cambridge University Press. Marsden, P.V. and N.E. Friedkin. 1994. “Network Studies of Social Influence”. In: Stanley Wasserman and Joseph Galaskiewicz (eds.), Advances in Social Network Analysis: Research in the Social and Behavioural Sciences. London: Sage Publications. Milroy, James. 1992. Linguistic Variation and Change: On the Historical Sociolinguistics of English. Oxford etc. Blackwell. Milroy, James & Lesley Milroy. 1985. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. London etc.: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Milroy, James & Lesley Milroy, 1997. “Network structure and linguistic change”. In: N. Coupland & A. Jaworski (eds.), Sociolinguistics: A Reader and Coursebook. London: Macmillan. Milroy, Leslie, 1994. “Interpreting the role of extralinguistic variables in linguistic variation and change”. In: G. Melchers & N.L. Johannsson (eds.), Nonstandard Varieties of Language. Stockholm: Alqvist & Wiksell. 131-145. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. http://www.oxforddnb.com/. Sutherland, J. 1969. English Literature of the Late Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Swales, J. 1988. “Discourse communities, genres and English as an international language”. World Englishes 7/2. 211-220. Wilke, H.A.M. (ed.). 1985. Coalition Formation. Advances in Psychology 24. New York & Oxford: Elsevier Science Publishers. Willer D. and B. Anderson (eds.). 1981. Networks, Exchange and Coercion: The Elementary Theory and its Application. New York & Oxford: Elsevier Science Publishers. Zeggelink, E. 1994. “Dynamics of structure: an individual-oriented approach”. Social Networks 16. 295-333.

Footnotes [1] For details, see Fitzmaurice (2004a), and other references. [2] To introduce a degree of flexibility into the characterisation, I have judged each parameter for each relationship on a five-point scale. The overall calculation of “proximity” is then a mean of the aggregated scores: greatest proximity = 1, least proximity (greatest distance) = 5. [3] For a detailed account of the quarrel, see Chapter 3 of Fitzmaurice (2002). [4] Although this is an essay, it has the look and feel of a sermon, in which the speaker invokes the congregation’s experience and beliefs and yokes those with her/his own.

|

|

|