Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics

Up |

|

A social network study of the eighteenth-century Bluestockings:

the progressive and preposition stranding in their letters 1 Anni Sairio (contact) (University of Helsinki) Received: December 2007, published December 2008 (HSL/SHL 8)

1. Introduction In September 1781, Elizabeth Montagu wrote to Elizabeth Vesey:

She was looking back to the three decades they had spent as part of the Bluestocking coterie, a social circle dedicated to polite and scholarly entertainment. This circle consisted of former statesmen, poets, scholars and educated gentry women, and Elizabeth Montagu (c. 1718–1800) was one of its most central figures from the early 1750s onwards. Montagu was an ambitious woman of intellect and wealth, and these characteristics combined eventually made her one of the most influential social hostesses and patrons in London. This paper analyses the structure and contents of Elizabeth Montagu’s Bluestocking network with particular detail to methods and sources, considers the network in terms of the spread of innovations and discusses language change in their correspondence over several decades from the point of view of social network analysis. Scholarly pursuits dominated these friendships and assemblies. The Bluestocking network itself was most visibly maintained in London salons, but because of the geographical mobility of the people involved it was also sustained by correspondence and visits (Myers 1990, Pohl and Schellenberg 2003). Women controlled membership in the circle to a great extent by deciding who would be invited to their salons and assemblies. According to Guest (2003:60), the term bluestocking in its broadest sense “refers to women who are socially prominent not because they are aristocratic, and not always because they are wealthy, but because of their learning, because they are women of letters”. In addition to Montagu, Elizabeth Vesey (1715?–1791) and Frances Boscawen (1719?–1805) were other notable hostesses, while Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806), Hester Chapone (1727–1801), and in the later years Hannah More (1745–1833) can be named as particularly distinguished female writers and scholars of the circle. Author and former statesman George, Lord Lyttelton (1709–1773), scholar and botanist Benjamin Stillingfleet (1702–1771) and former statesman William Pulteney, Lord Bath (1648–1764), were among the most notable men in the Bluestocking circle. Fanny Burney’s memoirs suggest that Elizabeth Vesey adopted the term as the name for the assemblies, and Benjamin Stillingfleet’s modest attire of blue worsted stockings may have been the origin of the expression (Pohl and Schellenberg 2003:3, Myers 1990:251). When the term was first coined in the 1750s, it was used to refer to men only. During the 1770s a gender shift took place in its meaning, and from then on women were more often the objects of the term, and in an increasingly derogatory sense (Myers 1990:6, 9–10). For the Bluestockings themselves, the term had a positive connotation. Elizabeth Montagu wrote to Elizabeth Vesey in 1768:

The linguistic features investigated in this paper are the progressive and preposition stranding. The progressive was still a relatively novel item at the time and was in the process of being established (Rissanen 1999, Strang 1982), whereas preposition stranding, an old construction in the English language, began to be stigmatised during the eighteenth century (Fischer 1992, Yáñez-Bouza 2006, 2008). I discuss the diachronic developments in the use of these items between 1738 and 1778, and consider language change in the Bluestocking letters in terms of innovativeness and possible network influence (Rogers 1983). The linguistic research and part of the network reconstruction is based on the Bluestocking Corpus, which has been compiled on the basis of a selection of manuscript letters and is suitable for sociolinguistic research (for the contents see Tables 1 and 2 in the Appendix; see also Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 1996, Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003). At the time of writing the corpus consisted of 196 original letters from the Montagu Collection (MO) in the Huntington Library and Add. 40663 in the British Library and another 24 letters from Eger’s (1999) edition. Its size is approximately 151,000 words 2, and it spans a period of forty years from 1738 to 1778 in four sub-sections.

2. The reconstruction and analysis of Elizabeth Montagu’s Bluestocking network 2.1 Background The research covers four time periods of four to six years each that range from 1738 to 1778. Networks are dynamic and change over time, so each time period requires a separate analysis. The four time periods (1738–1743, 1757–1762, 1766–1771 and 1775–1778) have been selected on the basis of significant events in Elizabeth Montagu’s life (see Myers 1990, Pohl and Schellenberg 2003, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, esp. Schnorrenberg 2004). A brief biographical description will explain the focus on these particular years in her life. The daughter of a landed gentry family, though one of relatively modest income, Elizabeth Robinson Montagu made her way to become one of the wealthiest and socially most influential women in London. As a girl, she was educated by her step-grandfather Dr. Conyers Middleton (1683–1750), a Cambridge classical scholar and author, and in the late 1730s and early 1740s, when Elizabeth was in her twenties, she spent much time in the home of her friend Lady Margaret Bentinck (1715–1785), the Duchess of Portland and the only daughter of the 2nd Earl of Oxford. The Duchess of Portland introduced her to the high society of London and was a personal example to Elizabeth of a salonnière. Elizabeth’s marriage in 1742 to the wealthy MP Edward Montagu (1692–1775), grandson of the first Earl of Sandwich, enabled her to become a hostess in her own right, and she was also able to provide various kinds of support for her family from then on. Furthermore, she came to have a considerable part in the Montagu coal mining business (on Elizabeth Montagu as a businesswoman, see Child 2003). Her girlhood years and involvement in the social circle of the Duchess of Portland in the late 1730s and early 1740s are discussed in comparison to her later Bluestocking years. Most Bluestocking friendships derived from spa town acquaintances made in the late 1750s, and the friendships were further strenghtened during the 1760s. In 1760 Montagu became an author by contributing three anonymous dialogues to Lord Lyttelton’s Dialogues of the Dead, and nine years later she published An Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear, which brought her considerable fame as a Shakespeare critic (see Eger 2003). During the writing process of both of these works she collaborated with her closest Bluestocking friends, particularly Lyttelton, Carter and Stillingfleet. In the late 1770s Montagu, then known as the “Queen of the Blues”, was publicly acclaimed in poetry and painting along with other eminent women. Edward Montagu’s death in 1775 had left her an immensely wealthy widow, and she subsequently granted annuities to Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806) and her sister Sarah Scott (1720–1795). The Bluestocking assemblies, too, grew in size and significance in the 1770s, and a second generation of Bluestocking women emerged, among them Fanny Burney (1752–1840), Hester Lynch Thrale (1741–1821) and Hannah More (1745–1833). The central Bluestocking men had passed away by that time. In 1775 the novelist Fanny Burney recorded in her journal a conversation between Samuel Johnson and Hester Thrale, Johnson’s confidante and another social hostess, concerning Montagu’s approaching visit to the Thrales:

Johnson and Montagu were not the best of friends, and the lexicographer never had any qualms about criticising people, so Burney’s record probably reflects a genuine respect towards the “Queen of the Blues” despite the tone of the conversation. 2.2 Sources and methods For the reconstruction of Montagu’s closest networks, I have tracked her social contacts through time with the help of contemporary studies and historical documents. This study has benefited from previous studies such as Granovetter (1983), Vickery (1998), Fitzmaurice (2002), Smith (2002), Bergs (2005) and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2008). I have used two biographical letter collections of her correspondence (Climenson 1906 and Blunt 1923), letter editions and biographies of other Bluestockings and their contacts (Pennington 1809, Llanover 1861), recent studies on Montagu and the Bluestockings (Myers 1990, Eger 1999, Pohl and Schellenberg 2003, Clarke 2005) and the manuscript letters I have been able to access. Personal networks can extend indefinitely through society via branching network ties, so a practical solution is to focus on first-order network ties which are the direct and most frequent contacts. My research focus has also inevitably been affected by the letters still available by network members: a thorough network analysis without material to test it on is not particularly useful. Letter-writing in the eighteenth century served as a significant source of news and a means to maintain relationships, so this alone provides a lot of information on Montagu’s social contacts and visits. In most cases it has been possible to determine how and when or by what time those connections were made. Elizabeth Carter was the most serious scholar of the Bluestocking women and the most highly regarded learned woman in England (Clarke 2005:26), and Montagu actively set out to form an acquaintanceship with her after Carter’s translation of Epictetus appeared in 1758 (Myers 1990:189–191). Montagu described her to Sarah Scott in 1758 as follows: “Miss Carter is to dine with me tomorrow; she is a most amiable, modest, gentle creature, not hérissée de grec, nor blown up with self-opinion” (quoted in Eger 1999:lix). Examples like these allow us to determine that by this time the two women had formed a personal acquaintance, and that Montagu was very pleased by this. Carter herself wrote to her close friend Catherine Talbot (1721–1770) in June 1758:

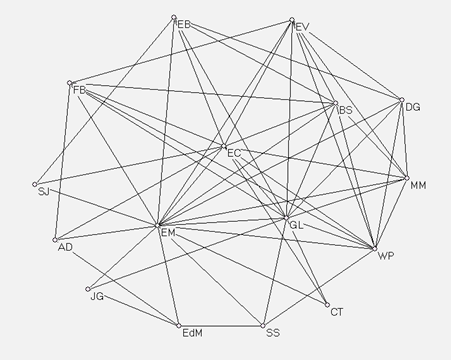

Thus we can tell that Carter, too, considered their relationship to be agreeable, and that Elizabeth Montagu was also acquainted with Talbot by the summer of that same year. As a result of this investigation I have created a database of what seem to have been Montagu’s most frequent contacts and her geographical mobility from 1738 to 1778, categorised into the four periods that correspond with the Bluestocking Corpus (see Sairio forthc. b). The database enables me to keep track of time lines, contacts, visits and overall records of correspondence. Information on other current activities has also been noted. 2.3. The structure and contents of the Bluestocking network The general structure and contents of the Bluestocking network will be briefly discussed next. Density, multiplexity and the strength of ties are the most common categories used to characterise network structure and contents (Milroy 1987, Bax 2000). The focus of this analysis will be on these factors. The concept of density refers to the frequency of network ties with regard to the number of potential ties that are realised in the network. Multiplexity describes the actual contents of the ties. Close-knit networks consist of strong network ties, whereas loose-knit networks are correspondingly made up of weak ties. Main sociolinguistic variables (age, gender, social class, education, geographical background, social mobility) are also considered in the overall analysis; this paper briefly describes the demographic categories of rank, age and education. Density defines the extent to which network members are connected to each other out of all the possible connections they might have. A high degree of density in which a large number of potential ties are realised allows for greater communication and the development of and exposure to group norms: this also implies how quickly or slowly information can be expected to diffuse in the network. Most Bluestockings knew each other personally and were relatively frequently in touch with each other, so the network was very dense. This is demonstrated in Figure 1, which presents the overall network structure of the year 1760. Centrality refers to the network prominence of an individual on the basis of the number of links which connect them directly to others (see e.g. Smith 2002:138); Figure 1 shows that Elizabeth Montagu (EM) was one of the most widely connected network members. She expanded her network to include people whom she considered interesting and actively promoted those under her patronage. Other particularly central figures were Elizabeth Carter (EC) and Lord Lyttelton (GL). Donnellan, Gregory, Johnson, Scott, Talbot and Edward Montagu have been included as fringe members.

Figure 1. The Bluestocking network in 1760. EM=Elizabeth Montagu, EC=Elizabeth Carter, EB=Edmund Burke, FB=Frances Boscawen, AD=Anne Donnellan, DG=David Garrick, JG=John Gregory, SJ=Samuel Johnson, GL=Lord Lyttelton, EdM=Edward Montagu, MM=Messenger Monsey, WP=Lord Bath, SS=Sarah Scott, BS=Benjamin Stillingfleet, CT=Catherine Talbot, EV=Elizabeth Vesey. A multiplex network tie consists of various elements, such as kinship, friendship and work relationship, whereas a uniplex network tie consists of one element only. The Bluestocking relationships were primarily based on friendship, literary collaboration and varying degrees of support and patronage; friendship here refers to an essentially intimate, warm and reciprocal but perhaps also an instrumental relationship (see Tadmor 2001:167–215). Collaboration within the network meant reading and commenting on each other’s works and helping with, for example, the printing process. This might also be thought of as a coalition in the sense that Fitzmaurice (2000) discusses Joseph Addison’s Spectator project: an instrumental alliance purposefully formed for a particular goal. However, Bluestocking collaboration derived from existing ties that were at some point used for joint ventures, so the ties were not purposefully created for alliances. Considering the density of the network, the multiplex contents of the network ties and the frequency of interaction, tie strength of ties between central Bluestockings is assumed to be strong (in Sairio forthc. a and b I present a network strength scale for quantifying the strength of ties). Strong network ties imply that information within the network is diffused quickly and efficiently, and that consequently there is a lot of shared knowledge as well as a propensity for shared group norms. Weak ties on the other hand function as bridges through which new information spreads from one network cluster to another. In a society with very few weak ties, innovations spread slowly and there is a real danger of stagnation (Granovetter 1983:2). However, social circles such as the Bluestockings are not threatened by this because of their social and geographical mobililty, which connects them to several other networks. The Bluestockings can be viewed as a cluster within the larger social circle of learned genteel people of eighteenth-century England. The network members have also been categorised in terms of the sociolinguistic variables social class, age and education. In terms of rank, the Bluestockings hailed from gentry and aristocratic families: the women’s background was mostly lower gentry, whereas nearly all the aristocrats were men. They were mostly middle-aged and older; the women were generally younger than the men by a decade or more. They were also well educated in that most men had received a classical education, whereas the women had been taught within the family and continued to school themselves.

3. Innovations and adopter categories Rogers and Kincaid (1981:90) argue that people’s behaviour is partly a function of the communication networks of which they are members. Network communication is particularly significant when individuals wish to reduce their uncertainty about a new idea (changing language use for example), for that is when they “depend heavily on interpersonal communication messages that are transmitted through networks” (Rogers and Kincaid 1981:90). I have used Rogers’s (1983:248-251) categorisation of innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards to characterise and categorise the Bluestockings. This is a twentieth-century model derived from the social sciences, so it has been applied to an eighteenth-century network with due caution; however, the main elements are still assumed to apply. Innovators can be characterised as marginal contacts who are connected to the network by weak ties. Having relatively little to lose and not much in the way of responsibility towards other network members, they are in a better position to take risks in an early stage of change than central network members, and they generally introduce new ideas and practices. Early adopters are integrated into the social system with strong network ties. They have a central position and more power in the network than innovators, and they are generally looked upon as opinion leaders whose comments are listened to by others. People classified as belonging to the early majority on the other hand are rarely in a leadership position, but they interact frequently with their social group and react to changes slightly before average. Late majority and laggards are relatively hesitant and conservative, even hostile, in their attitudes towards change, and they are the last to react to or adopt innovations, if they do so at all. Valente (1996:80) notes that they may also remain outside the scope of external influence through which others learn of innovations and which encourages them to adopt such innovations. Twentieth-century research in the social sciences indicates that earlier adopters are generally more educated and more literate and have a higher social status and a greater degree of upward social mobility than later adopters. Also, earlier adopters are apparently “not only of higher status but are on the move in the direction of still higher levels of social status” (Rogers 1983:251). However, it should be noted that an individual’s reactions to innovations and change are likely to vary depending on factors such as network thresholds (see Valente 1996). On the basis of the threshold model, Valente (1996:73) states that interpersonal influence is a crucial factor in the diffusion of innovations in a social network. When these categories are applied to Montagu and her network contacts over time, it seems that we might be mostly looking at potential early adopters and early majority. The Bluestocking network consisted of strong ties and it was very dense, so the interaction between network members was frequent and varied. It follows that the circle was likely to have included opinion leaders whose example or verdicts were observed in new situations, and when accepted by these people, changes may have spread rapidly through the network. There may also have been persuasion to adopt group norms, and individuals were probably aware of other network members’ attitudes towards innovations. Overall, Elizabeth Montagu would not have been a radical innovator. In her youth she was probably influenced a great deal by the example of the Duchess of Portland, at least until her marriage in 1742, and perhaps also after that. Her family and her husband would also have provided her with a linguistic model. From the 1750s onwards, if we accept Rogers’s claim that earlier adopters are in general of higher status but also social risers on the move (1983:251), Elizabeth Montagu could be characterised as belonging to the category of early adopters or the early majority. As an integrated network member who already in the 1750s was a contact builder and one of the central Bluestockings, she might not have been willing to accept the risks inherent in being an innovator. The same probably also applies to other central Bluestockings. It does not seem probable that this tight-knit group of fairly conservative gentry people would have led the first wave of linguistic innovations. Raumolin-Brunberg (2006) shows that during the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries linguistic innovations originated in the lower social classes, whereas the leaders of the second phase of change mostly represented the influential upper classes of London and the court. It is overall more probable that the Bluestockings acted as the network’s early adopters and opinion leaders, or as early majority. Early adopters have also shown to have more sources of external influence (Valente 1996:74), which fits well with the overall activities of the Bluestockings. Considering the social structure of the group, the aristocrats, most of whom were men and had received a classical education, may have been considered as opinion leaders. Despite her central position in the network, Montagu’s gender and the social implications and restrictions it entailed may have caused her to be more hesitant than early adopters and early majority in reacting to innovations, and more inclined to look at the example of her peers and superiors.

4. The progressive and preposition stranding as case studies Language change and the possible influence of network ties in the Bluestocking Corpus are now considered with regard to the progressive construction and preposition stranding. These constructions complement each other in the eighteenth-century context, as both can be expected to show change in the course of the century, although in different ways. Example (1) demonstrates Sarah Scott’s use of the progressive to inform Montagu that their sister-in-law was expecting a child.

Example (2) demonstrates preposition stranding in an early letter of Elizabeth Montagu to her husband.

The seventeenth century was a crucial period in the development of the progressive, and by the end of the eighteenth century it had developed in all tenses (Rissanen 1999:216; see also Strang 1982 and Kranich 2007). It was still a fairly novel construction, but it increased in frequency during the century as it was used in a wider context than before. The progressive was only mildly commented upon by grammar writers of the eighteenth century, except for the progressive passive (Beal 2004:78, Rissanen 1999:218). Robert Lowth notes in the Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762:55–56) that “in discourse we have often occasion to speak of Time [...] as passing, or finished; as imperfect, or perfect”, denoting definite or determined time, as in I am (now) loving, I was (then) loving, and I shall (then) be loving. He does not make particularly evaluative remarks with regard to the use of the construction apart from observing that these constructions were used in “discourse” contexts, i.e. speech. Fitzmaurice (2004) discusses the use of the progressive in the texts of an early eighteenth-century English social network. Outsiders in the network seem to use the progressive in different frequencies than those on the inside, and Fitzmaurice’s results suggest that network membership along with the gender and socioeconomic status of the writer might condition experimental and/or subjective progressive constructions (2004:161). Arnaud (1998:128) shows that gender and intimacy play an important role in the use of the progressive in private letters of the late eighteenth to late nineteenth centuries. The higher the degree of intimacy between writer and recipient, the more frequently the progressive occurred; also, women seemed to be more open to its use than men. A previous study of the progressive in the Bluestocking letters (Sairio 2006) shows that Montagu used the be+ing construction considerably more frequently in her letters to friends than to family, possibly attempting to create a feeling of immediacy with the correspondent in question. Preposition stranding on the other hand had been present in the language since the Old English period. It was extended to wh-relative clauses and questions in the thirteenth century (Fischer 1992:390), and became a real alternative to pied piping (or preposition fronting) in wh-relative clauses during the Early Modern period (Bergh and Seppänen 2000:309). In present-day English, preposition stranding is found in the following syntactic constructions (Huddleston and Pullum 2002:627):

In several of these constructions preposition stranding is in fact grammatically required, but in preposing, open interrogatives, exclamatives and wh-relative clauses, so in constructions i, ii, iii and iv, there is a possibility for variation between pied piping and preposition stranding (Huddleston and Pullum 2002:627). During the eighteenth century, attitudes towards preposition stranding were becoming increasingly hostile. John Dryden expressed his discontent towards it in the late seventeenth century (Yáñez-Bouza 2006), and the construction was condemned by several eighteenth-century grammarians as vulgar language use and a violation of logic (Yáñez-Bouza 2008). Although grammarians did not explicitly say so, the etymology of the term preposition and the influence of Latin syntax are probable reasons why pied piping was generally preferred over preposition stranding (Beal 2004:110). This was the case despite the fact that preposition stranding was, and still is, the only syntactically correct choice in several environments (see construction v-viii above). Possibly as a result of changing notions of stylistic appropriateness, the ratio of preposition stranding vs. pied piping in wh-relative clauses dropped in standard written usage from 12% in Early Modern English to 2% in Late Modern English (Bergh and Seppänen 2000:312). Furthermore, end-placed prepositions in the Century of Prose Corpus are shown to have decreased from 23.3 per 10,000 words in 1680–1740 to 11.7 in 1740–1780 (Yáñez-Bouza 2006). Contrary to Lowth’s subsequent reputation as a strict prescriptivist, he was in fact rather mild and descriptive in his view on preposition stranding in relative clauses, as has been pointed out by Tieken-Boon van Ostade. Yáñez-Bouza (2008) also points out that unlike is often assumed, he was not the first language authority to criticise preposition stranding: John Mason had already condemned it in 1749 in his Essay on the Power and Harmony of Prosaic Numbers. Lowth (1762:127) states that in English “this is an idiom which our language is strongly inclined to; it prevails in common conversation” (famously expressing himself with preposition stranding; see e.g. Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2006), and thus agreeing to its use in the familiar style in writing. Nevertheless, he prefers pied piping as being “more graceful [and] perspicuous”, also because it “agrees much better with the solemn and elevated Style” (1762: 128). Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006) shows that Lowth, indeed, used preposition stranding in his private informal letters to friends and relatives. As educated literary people, many of whom were published writers, the Bluestockings were likely to have been aware of contemporary views on proper language use and, up to a point, conscious of their own language use. Elizabeth Montagu, as an educated woman and author, a successful social riser and an increasingly public figure, was probably aware of both aspects. According to Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006), Lowth’s private letters show that the norms he advocated in his grammar did not derive from his own language, particularly in the case of preposition stranding. Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006) proposes that the linguistic norm at the basis of Lowth’s grammar in fact reflected his perceptions of upper-class language use. If Lowth looked to the upper classes for a model, perhaps Elizabeth Montagu did the same. In addition to network ties, social class is also considered as a separate category in the analysis presented here. For the purposes of this study, all the progressive constructions (except for gerundial forms and be going to constructions) and eleven high-frequency prepositions for, to, of, in, on, into, at, upon, from, by and with were retrieved from the Bluestocking Corpus both in stranded and fronted positions. The focus in this paper is on preposition stranding, and pied piping is considered only in overall frequencies.

5. The progressive in the Bluestocking letters Examples (3)–(5) illustrate the use of the progressive in the Bluestocking Corpus. (3) and (4) demonstrate situational immediacy in which the writer invites the recipient to participate in the moment of writing (Sairio 2006:184, Rydén 1997:421), and they also represent Arnaud’s “super-present” progressive that suggests warmth, sensibility and expressiveness (1998:144). Example (5) shows an active progressive used for passive meaning; the passive form (the horses were being put to) emerged only at the end of the eighteenth century (Rissanen 1999:218).

Table 4 shows that the progressive is a low-frequency variable, which nevertheless shows a slight tendency of increasing in epistolary language use. There is a temporary reduction from 9.9 (per 10,000 words) to 7.6 between the first and the second time periods, after which the frequencies rise again. Montagu’s letters are the most reliable material from an individual writer. Her use of the progressive shows a slight increase from 9.0 in the first time period to 11.2 in the last time period. In the letters of the other individual informants the frequencies are too low for more detailed analysis; suffice it to say that the progressive appears to have been very infrequent indeed, as it is not used more than 7 times in a selection of over 13,000 words (Sarah Scott’s letters). A study of the use of alternative verb constructions might shed more light on the matter.

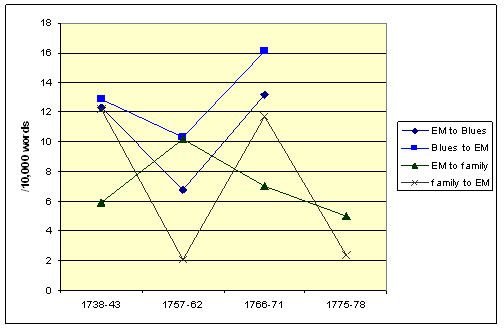

Table 4. The progressive in the Bluestocking corpus. (frequencies normalised to 10,000 words (>5) and absolute figures). To consider the recipient registers in Montagu’s letters, the majority of 68% (75) of her progressives appear in her letters to friends and 32% (36) in her letters to family members. The progressive is used more frequently in her correspondence to friends in every time period, and the overall variation is statistically significant (p<0.025). Gender on the other hand does not factor considerably in the use of the progressive, as only minor and insignificant variation was observed. Register variation is next considered in terms of sender/recipient relationships. Montagu’s out-letters to the Bluestockings were separated from those she wrote to her family, and her in-letters were respectively grouped into Bluestocking and family correspondence. For the sake of convenience, her friends the Duchess of Portland (1715-1785) and Anne Donnellan (1700-1762), who was another important friend and correspondent, are included as Bluestocking recipients for the years 1738-1743. Donnellan, an Irish-born gentry woman, was an influential figure in Elizabeth’s life at this time, and she encouraged Elizabeth to educate herself further. She also visited the Bluestocking assemblies in the years to come. Figure 2 demonstrates the results of this regrouping.

Figure 2. The progressive according to sender/recipient relationship. Figure 2 indicates that there may have been a connection in the way Montagu and her Bluestocking friends use the progressive, demonstrated by the similar rising curves and the dip in the second time period which does not occur in Montagu’s letters to her family. This dip in Montagu’s out-letters to the Bluestockings may result from some sort of linguistic insecurity or stylistic factors controlled by the level of intimacy and familiarity in their relationships. To consider the first explanation, in 1757–1762 Montagu was still in the process of establishing herself as one of the intellectual London hostesses and actively creating some of her most important friendships with men and women of scholarly distinction, while she had also published her first works in 1760 (albeit anonymously). Furthermore, the dip in her use of the progressive seems to have concerned her aristocratic correspondents only, with a mere two occurrences in over 10,000 words to these recipients vs. the normalised figure of 10.1 (25) in the letters to the lower gentry correspondents. Linguistic hesitancy as a possible explanation might be further affirmed by Montagu’s considerably more infrequent use of the progressive in her letters to the aristocrats (3.5) compared to the aristocrats’ own use of the construction (6.7) during 1757–1762. If the dip does result from her being more careful in this particular period, it is interesting that she does not appear to have been as concerned with her language use in her early twenties as at other stages in her life. The decrease might also result from stylistic variation in Montagu’s letters. Examples (3) and (4) illustrate the progressive as a distance-reducing means to report on ongoing activity at the time of letter-writing and to create an experience of immediacy, and it is possible that her closest non-family relationships in the late 1750s were not on such familiar grounds as to warrant this relatively informal style of writing. Using the progressive as a distance-reducing item may have been less likely also for her Bluestocking friends in the late 1750s and early 1760s, when their friendships were still relatively new. This explanation would also correspond with the particularly reduced frequencies in Montagu’s letters to her aristocrat friends, with whom her relationship was less equal. Perhaps because the progressive was a fairly new construction and there may not yet have been a particular niche for it, some of the writers in the Bluestocking Circle seem to have been ambiguous about its use, especially Sarah Scott, who uses the be+ing construction very scarcely considering the number of her letters in the corpus. It is mainly because of Scott that the progressives in the family letters to Montagu in Table 4 vary so drastically in the course of the years. It appears that the sisters did not share particularly similar stylistic patterns in this respect, whereas Montagu and the Bluestockings seem to have had a more common general pattern in their respective language use. Figure 2 suggests that Montagu was generally less inclined to choose a progressive construction than the Bluestockings but that she followed the general increasing pattern set by her friends. This indicates that some sort of language accommodation and network influence may have been at work, and perhaps also reflects a growing familiarity in their relationships which resulted in an increasing number of progressives as conveyors of immediacy. Ideally, to investigate the use of the progressive by individual writers the respective frequencies in the correspondence between Montagu and the other letter-writers should be compared in order to see if the figures are similar and what sort of diachronic developments take place in these reciprocated correspondences. The frequencies are nevertheless so low that analysis broken down to individual informants would not be reliable. Figure 3 therefore compares the overall frequencies of the progressive in Montagu’s out-letters and in the respective in-letters from all her correspondents. The fourth time period has been omitted from the analysis as the in-letters contain only one case of the progressive.

Figure 3. The progressive in overall reciprocated correspondence. Figure 3 shows that Montagu uses the progressive less than her correspondents in two out of three time periods. In 1738–1743 and in 1766–1771 the construction appears considerably more often in the letters she received from her correspondents, but the differences are not statistically significant. During the first time period, most of Montagu’s correspondents were her superiors in terms of rank and family hierarchy, and different levels of distance with regard to stylistic choices and some kind of linguistic insecurity may both serve as explanations. In 1757–1762 the dip appears in both sets of letters, and the difference temporarily evens out.

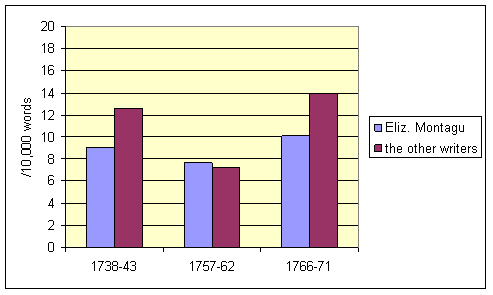

Figure 4. The progressive and the social class of the writers. Figure 4 shows the occurrences of be+ing as divided according to the social class of the writers. The writers are divided into lower gentry and nobility, and Montagu is considered separately from the other lower gentry informants due to her otherwise considerable influence on the overall results and also in order to compare her with her correspondents in terms of rank. The aristocratic writers use the progressive the most, which suggests that they were more inclined to use this fairly informal feature in their letters to a female friend than Montagu’s correspondents who shared the same social background; perhaps they were generally even more open to the use of a novel linguistic item than the lower gentry writers. However, the differences are not statistically significant. In Montagu’s letters the progressive is approximately as frequent as in the letters of her lower gentry correspondents. To conclude, the progressive increased slightly over the years, which may have resulted both from a generally increasing use of the form and from the growing familiarity and informality in the network ties between these writers, two explanations which in themselves may be connected. Bearing in mind that the low figures allow only for tentative conclusions, it is possible that Montagu may have accommodated her language use to that of her Bluestocking friends, who used the progressive much more than her family; immediacy and the writers’ possible wishes to diminish distance between themselves and their recipients also seem to be linked in the use of this construction. Register is a considerable factor behind the use of the progressive in that Montagu’s letters to friends contain significantly more instances of this construction than letters to family members. In terms of the innovator categories, Montagu appears to have been more of a follower, whereas the aristocrats might have been the most innovative users, be that for purposes of immediacy or in terms of generally increasing use of the progressive.

6. Preposition stranding in the Bluestocking letters Different types of this construction in the Bluestocking Corpus are presented in examples (6)–(12). Examples (6) and (7) demonstrate preposition stranding in wh-relative clauses, (8) and (9) in Ø relative clauses, (10) in a passive clause and (11) with a prepositional verb. (12) is an example of preposing, which in principle allows pied piping as an alternative, as do examples (6) and (7).

In overall figures, preposition stranding and the progressive are approximately equally common constructions in the Bluestocking Corpus. But while the progressive increased slightly over the years, Table 6 shows that there was a clear reduction in the use of preposition stranding from 13.4 to 5.3, with a significant decrease from the first time period to the second (p<0.001). Pied piping also increased considerably from 8.3 to 15.1 (pied piping in the Bluestocking Corpus is considered in more detail in Sairio 2008 and forthc. b). Preposition stranding makes up for 39% (131) and pied piping for 61% (207) of the cases. The significant drop in the use of this increasingly criticised construction appears to co-occur with the considerable popularity of grammar books in the 1760s (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2008). Zero relative clauses, passive clauses and prepositional verbs are the most frequent contexts for preposition stranding in the Bluestocking Corpus, and these grammatically obligatory constructions make up 83% of all the cases. In other words, pied piping would not have been an option for the majority of these items.

Table 6. Preposition stranding and pied piping in the Bluestocking Corpus. Table 7 presents the diachronic developments of preposition stranding in the letters of individual informants and shows that this, too, was a low-frequency item. The most reliable figures are found in Elizabeth Montagu’s letters, in which preposition stranding decreased from 14.6 in 1738–1743 to 2.7 in the late 1770s. Sarah Scott’s letters are the only other set of material which contains more than just a handful of occurrences: these letters suggest that Montagu may have been more strict in her growing avoidance of the construction than Scott. At any rate, preposition stranding was much more frequent in Scott’s letters than the more neutral progressive, which may suggest that at least in her informal family correspondence Scott was not particularly innovative or prone to change in her language use, be that in terms of adopting a relatively new feature or discarding an old increasingly stigmatised one.

Table 7. Preposition stranding per informant and time period (frequencies normalised to 10,000 words (>5) and absolute figures).

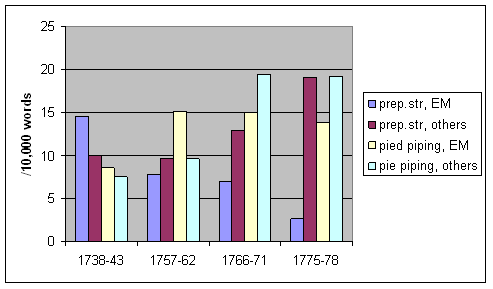

Figure 5. Preposition placement in the Bluestocking Corpus. Figure 5 presents the normalised frequencies of preposition stranding and pied piping in Montagu’s letters and in the other letters of the corpus. A general comparison shows that preposition stranding in Montagu’s letters was reduced considerably over the years while pied piping increased, whereas in the letters written to her both constructions seem to have increased. However, the absolute figures in the in-letters make up altogether only 44 instances of pied piping and 40 of preposition stranding, so not a lot can be read into these results. In total frequencies, Montagu used preposition stranding considerably but not significantly less frequently than her correspondents (7.9/93) vs. 11.8/40) and pied piping approximately in the same frequencies (13.6/160 vs. 13.0/ 44). Overall, pied piping in Montagu’s letters occurred in 66% of the cases, whereas 34% of the prepositions in question were in a stranded position. Preposition stranding was more frequent in Montagu’s letters than pied piping only during the first time period (14.6 /34 and 8.6/20, respectively). Figure 5 shows that pied piping seems to have been stabilised in her letters after the leap from the first time period to the second; there was little variation after that, whereas preposition stranding seems to have been on its way out. As for the other writers considered together, preposition stranding was more common than pied piping in the first time period (10/8) and 7.5/6, respectively). Also in these letters pied piping was on the increase, though preposition stranding was not reduced. In fact, it increased steadily between 1757 and 1778, by which time it was used as frequently as pied piping. However, at this time the only writer is Sarah Scott, and with an absolute figure of eight for both items, the results are not reliable. It would seem, though, that Scott was not particularly concerned with the status of either of these constructions.

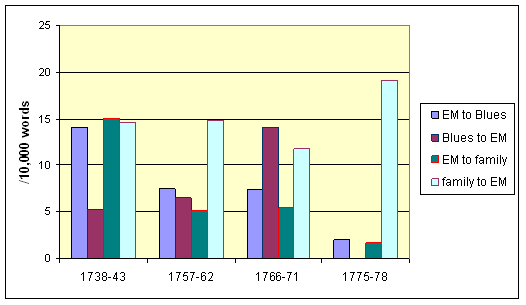

Figure 6. Preposition stranding according to sender/recipient relationship. In Figure 6 the results were again divided into four categories: Montagu’s out-letters to the Bluestockings and the in-letters from the Bluestockings, and letters to and from Montagu’s family members. Figure 6 shows that Montagu avoids preposition stranding fairly consistently from the second period onwards regardless of her relationship with the recipients, whereas both the Bluestocking writers and her family correspondents do not really appear to have reduced their use of the construction. Overall, network similarities in the use of preposition stranding seem to be implicit at the most. To consider the results in more detail, in 1738-1743 Elizabeth Robinson and her family used preposition stranding in similar frequencies (15.1 and 14.6, respectively), whereas the Duchess of Portland (again representing the Blues) avoided it considerably more (5.2). Preposition stranding occurs in similar frequencies in Elizabeth’s letters to her friends (14.1 in total) and her family (14.6). Even though this seems to suggest that she was not aware of or did not worry about the stigma associated with the construction, preposition stranding appears less frequently in her letters to the aristocratic Duchess (6.7) than in those to the gentry-born Anne Donnellan (22.3). In 1757–1762 the Bluestockings and Montagu used preposition stranding in fairly similar frequencies (6.5 and 7.5, respectively), but from this period onwards the numbers decrease both in Montagu’s letters to her family and to her Bluestocking friends, regardless of the frequency of preposition stranding in the letters from these groups. However, the figures are very low in the Bluestocking letters from 1766–1771 (having increased from 2 to 7) and do not allow for conclusions. Montagu’s family members do not share her tendency to avoid preposition stranding after the first time period. In 1775–1778, the construction occurs hardly at all in Montagu’s letters, whereas Sarah Scott (who represents family writers in the last time period) does not seem to avoid it. Except for the potential influence of Elizabeth’s family in 1738–1743 and the mutually low frequencies in the letters of Elizabeth, the Duchess of Portland and the Bluestockings in 1757–1762, indications of language accommodation are not clear.

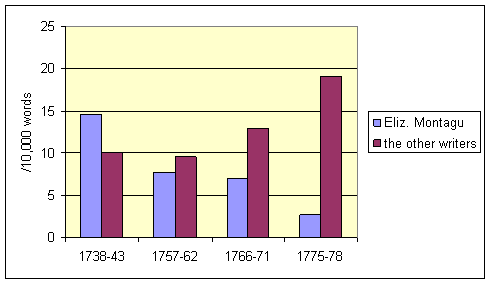

Figure 7. Overall preposition stranding in reciprocated correspondence. As was the case with the progressives, the absolute figures for preposition stranding for single writers are so low that it would not make sense to compare individual sets of letters. Figure 7 compares the overall frequencies per time period in Montagu’s out-letters and in the letters sent to her by the other writers in the Bluestocking Corpus. It appears that Montagu reduced her use of the construction regardless of the increasing figures in the in-letters she received from her correspondents, which suggests that, overall, there are no particular signs of language accommodation or network influence. Montagu may in fact have wanted to avoid even the syntactically obligatory constructions, as is suggested in Sairio (2008). However, the second time period 1757–1762 seems to suggest more similar patterns of language use between Montagu and her correspondents than what can be observed during the other time-periods, which would coincide with the simultaneous drop in their use of the progressive; perhaps this period of blossoming Bluestocking friendships resulted in some kind of (temporary) language accommodation. Next I will consider briefly preposition stranding in wh-relative clauses, which theoretically accept pied piping as an alternative. This construction is very infrequent and consistently less common than pied piping throughout the four decades, and by the late 1770s it is absent from Elizabeth Montagu’s letters altogether; see Sairio (2008, forthc. b) for further discussion of the diachronic developments of wh-relative clause preposition placement in the Bluestocking Corpus. Finally, the results are considered with regard to social class first in Figure 8 and then in Figure 9. Montagu is again excluded from the other lower gentry writers.

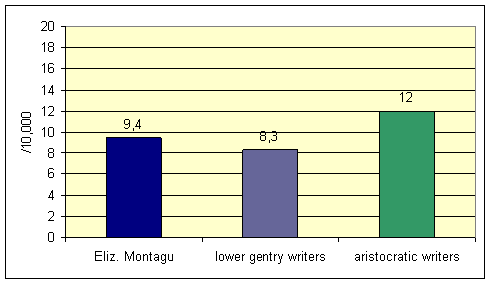

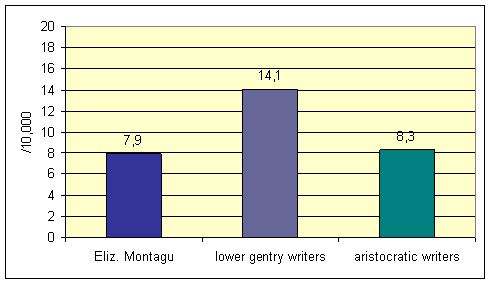

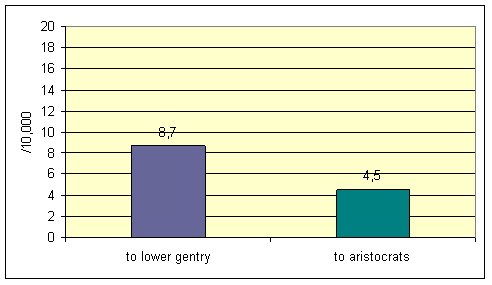

Figure 8. Preposition stranding and the social class of writers. Figure 8 shows that the lower gentry writers were the most likely to strand their prepositions. The total frequency of preposition stranding is 8.3 (11) in the aristocrats’ letters and 14.1 (29) in the lower gentry letters. Overall, the variation is not significant, but the results suggest that lower gentry writers, when writing to an equal in terms of rank, may have been more ready to use this construction, which was after all considered by Lowth (1762:128) to be a feature of common conversation. Figure 9 demonstrates preposition stranding in Montagu’s letters with regard to the rank of the recipients. Again, diachronic investigation of this variation is not feasible as the absolute figures are very low. Preposition stranding is more frequent in Montagu’s letters to people of a lower gentry background (8.7/83 instances) than to correspondents socially above her (4.5/10 instances), but the variation is not statistically significant. Nevertheless, that Montagu used preposition stranding less frequently in her letters to correspondents of higher social status indicates that there was a sort of class awareness present in her language with regard to particular contexts.

Figure 9. Preposition stranding in Montagu’s letters: rank of recipients.

7. Conclusion This paper demonstrates theoretical and practical aspects of applying social network analysis to a study of eighteenth-century English. Background work in establishing network contacts and analysis of the structure and contents of a social network have been presented, and the results of a corpus study have been analysed in terms of social network analysis and the sociolinguistic variables of register and social rank. Network ties were not found to be considerably influential in the epistolary use of either the progressive or preposition stranding, but there may have been common elements in the way Montagu and her Bluestocking correspondents used the progressive. Montagu herself was relatively hesitant in her use of the progressive, and the aristocrats appeared to be more innovative than lower gentry writers in general; this is perhaps linked to the increasing familiarity and the experience of closeness that certain functions of the progressive carried, and which Montagu’s aristocratic correspondents may have felt comfortable applying. In terms of the adoption process Montagu could perhaps be characterised as belonging to the late majority instead of earlier adopters, which her social position suggested. Sarah Scott seems to represent late majority or even that of laggards, and the sisters do not seem to have influenced each other linguistically. Perhaps gender is of essence here. Could women of Late Modern England have been considered as opinion leaders in language change? Perhaps their influence was more of a social than linguistic nature, taking also into account that women did not generally receive higher formal education. Henstra (2006) notes that gender is underrepresented in previous studies of network strength (Milroy 1987; Bax 2000), which should be considered in future research (see Sairio forthc. b). The stigma which preposition stranding carried seems eventually to have been more important for Montagu than the example of her network contacts. There were indications that social class influenced the use of preposition stranding, as Montagu used it carefully and avoided it even more when she wrote to those socially above her, like Lowth (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2006). Contrary to the use of the progressive, preposition stranding was also less frequent in the letters of aristocratic informants. As for the possible influence of grammars, preposition stranding was significantly reduced in Montagu’s letters when she began to establish herself as a Bluestocking hostess and author, but this took place before Lowth’s grammar first appeared in 1762. Perhaps the public discussion on preposition stranding had increased during the previous decades, which prompted Lowth to comment on the construction and Montagu to reduce her use of it. Yáñez-Bouza (2008) has shown that after Dryden, preposition stranding had been condemned in language treatises as early as 1749, and it seems that both Montagu and Lowth had picked up on this. Similar developments in the use of preposition stranding were not observed in the other letters besides Montagu’s, but as this is a low-frequency item, this may result from an insufficient amount of material from the other writers. Furthermore, Sairio (2008) shows that in wh-clauses preposition stranding was much less frequent than pied piping already in the late 1730s, which suggests that the criticism may have had an effect decades before the golden age of grammar writing, thus pointing to Dryden as the possible source of these developments. To conclude this paper, the influence of network ties might be partly connected to current attitudes to language use. The progressive was not condemned as bad usage, so Montagu perhaps looked to her most important peer group and followed their example in moderation. She was possibly aware that her Bluestocking friends (lower gentry and aristocrats alike) used preposition stranding fairly little in 1757–1762 and reduced her own use of the construction accordingly, but their later higher frequencies did not influence her any longer. Perhaps the network did not influence preposition stranding in Montagu’s letters once the decline was on its way. Elizabeth Montagu’s Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespear, Compared with the Greek and French Dramatic Poets, with some Remarks upon the Misrepresentations of Mons. de Voltaire (London) came out in May 1769, and the first edition was quickly sold out. It was published anonymously, but after the handwriting in the corrected prints had been recognised as Benjamin Stillingfleet’s, one of Montagu’s closest friends, rumours of her authorship began to spread. The Essay received fairly positive reviews from the Monthly Review and the Critical Review (Myers 1990:199–200), and various people wrote to Montagu to congratulate her on her success. Among these people were James Harris (1709–1780), author of Hermes (1751), and Hugh Blair (1718–1800), then a lecturer of rhetoric and belles lettres at the University of Edinburgh. Blair was also a personal acquaintance of Montagu’s. In June 1769, he wrote to her:

Incidentally, Blair was among the authors who strongly condemned preposition stranding (Yáñez-Bouza 2008). Becoming a published author in Lyttelton’s Dialogues of the Dead in 1760 and this more independent venture as a literary critic must have influenced Montagu’s consciousness of her language use, perhaps more than her network connections did. A compliment such as Blair’s must have increased her awareness of herself as a public persona and of her potential influence on others.

Table 1. The writers and word counts per time period in the Bluestocking Corpus.

Table 2. The recipients and word counts per time period in Elizabeth Montagu’s letters.

References Arnaud, René (1998). “The Development of the Progressive in 19th Century English: A Quantitative Study.” Language Variation and Change 10 (2). Bax, Randy C. (2000). “A Network Strength Scale for the Study of Eighteenth-Century English”. Social Network Analysis and the History of English: Special issue of EJES 4 (3). 277–289. Beal, Joan C. (2004). English in Modern Times. Oxford: Arnold. Bergh, Gunnar and Aimo Seppänen (2000). “Preposition stranding with wh-relatives: a historical survey”. English Language and Linguistics 4 (2). Bergs, Alexander (2005). Social Networks and Historical Sociolinguistics. Studies in Morphosyntactic Variation in the Paston Letters (1421-1503). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Blunt, Reginald (ed.) (1923). Mrs. Montagu, “Queen of the Blues,” her letters and friendships from 1762 to 1800. Edited by Reginald Blunt from material left to him by Emily J. Climenson. 2 vols. London: Constable & Co. Child, Elizabeth (2003). “Elizabeth Montagu, Bluestocking Businesswoman”. In: Pohl and Schellenberg, Reconsidering the Bluestockings. San Marino: Huntington Library Press. Clarke, Norma (2005). Dr. Johnson’s Women. London: Pimlico. Climenson, Emily J. (ed.) (1906). Elizabeth Montagu, the Queen of the Bluestockings: her correspondence from 1720 to 1761 by her Great-great-niece Emily J. Climenson. 2 vols. London: John Murray. Eger, Elizabeth (ed.) (1999). Bluestocking Feminism: Writings of the Bluestocking Circle, 1738-1785. volume 1. Elizabeth Montagu. London: Pickering & Chatto. [General editor Gary Kelly]. Eger, Elizabeth 2003. “‘Out rushed a female to protect the Bard’: The Bluestocking Defence of Shakespeare”, in Pohl and Schellenberg, Reconsidering the Bluestockings. San Marino: Huntington Library Press. Fischer, Olga (1992). “Syntax”. In: Norman Blake (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language. vol II. 1066-1426. New York: Cambridge University Press. Fitzmaurice, Susan (2000). “Coalitions and the Investigation of Social Influence in Linguistic History”. Social Network Analysis and the History of English: Special issue of EJES 4 (3). 264–276. Fitzmaurice, Susan (2002). “Politeness and modal meaning in the construction of humiliative discourse in an early eighteenth-century network of patron-client relationships”. English Language and Linguistics 6 (2). 239–265. Fitzmaurice, Susan (2004). “The Meanings and Uses of the Progressive Construction in an Early Eighteenth-Century English Network”. In: Anne Curzan and Kimberly Emmons (eds.), Studies in the History of the English Language II. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Granovetter, Mark (1983). “The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited”. Sociological Theory 1. 201–233. http://www.si.umich.edu/~rfrost/courses/SI110/readings/In_Out_and_Beyond/Granovetter.pdf. Guest, Harriet (2003). “Bluestocking Feminism”. In: Pohl and Schellenberg, Reconsidering the Bluestockings. San Marino: Huntington Library Press. Henstra, Froukje (2006). A Family Affair: Social Network Analysis and the language of the Walpoles. Unpublished MA thesis. University of Leiden. Huddleston, Rodney D. and Geoffrey K. Pullum (2002). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kranich, Svenja (2007). “Interpretative progressives in Late Modern English”. A paper presented at the 3rd Late Modern English Conference, University of Leiden, the Netherlands. Lady Llanover (ed.) (1861-1862). The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany: with interesting reminiscences of King George the Third and Queen Charlotte. 6 vols. London: Richard Bentley. Lowth, Robert (1762). A Short Introduction to English Grammar: with critical notes. London. [ECCO] Milroy, Lesley (1987). Language and Social Networks. Oxford: Blackwell. Myers, Sylvia Harcstark (1990). The Bluestocking Circle: Women, Friendship and the Life of the Mind in Eighteenth-Century England. Oxford: Clarendon. Nevalainen, Terttu and Helena Raumolin-Brunberg (eds.) (1996). Sociolinguistics and Language History. Studies Based on The Corpus of Early English Correspondence. (Language and Computers 15). Amsterdam & Atlanta: Rodopi. Nevalainen, Terttu and Helena Raumolin-Brunberg (2003). Historical Sociolinguistics: Language Change in Tudor and Stuart England. London: Pearson Education. Pennington, Montagu (ed.) (1809). A Series of Letters between Mrs. Elizabeth Carter and Miss Catherine Talbot, from the Year 1741 to 1770: To which are added, Letters from Mrs. Elizabeth Carter to Mrs. Vesey, between the Years 1763 and 1787. published from the original manuscripts in the possession of the Rev. Montagu Pennington. vol 1. London: F. C. and J. Rivington. Pohl, Nicole and Betty A. Schellenberg (eds.) (2003). Reconsidering the Bluestockings. San Marino: Huntington Library Press. Pohl, Nicole and Betty A. Schellenberg (2003). “Introduction: A Bluestocking Historiography”. In: Pohl and Schellenberg, Reconsidering the Bluestockings. San Marino: Huntington Library Press. Raumolin-Brunberg, Helena (2006). “Leaders of linguistic change in Early Modern England.” In: Roberta Facchinetti and Matti Rissanen (eds.), Corpus-based Studies of Diachronic English. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. 115–134. Rissanen, Matti (1999). “Syntax”. In: Roger Lass (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language. volume III: 1476-1776. Cambridge: CUP. Rogers, Everett M. & D. Lawrence Kincaid (1981). Communication Networks. Toward a New Paradigm for Research. New York and London: Macmillan. Rogers, Everett M. (1983). Diffusion of Innovations. New York and London: The Free Press. (third edition). Rydén, Mats (1997). “On the panchronic core meaning of the English progressive”. In: Terttu Nevalainen and Leena Kahlas-Tarkka (eds.), To Explain the Present: Studies in the Changing English Language in Honour of Matti Rissanen. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique. Sairio, Anni (2006). “Progressives in the letters of Elizabeth Montagu and her circle in 1738-1778”. In: Christiane Dalton-Puffer, Nikolaus Ritt, Herbert Schendl, and Dieter Kastovsky (eds.), Syntax, Style and Grammatical Norms: English from 1500-2000. Linguistic Insights, Frankfurt. Bern etc.: Peter Lang. Sairio, Anni (2008). “Bluestocking letters and the influence of eighteenth-century grammars”. In: Dossena, Marina and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade (eds.), Studies in Late Modern English Correspondence: Methodology and Data. Sairio, Anni forthc. a. “Methodological and practical aspects of historical network analysis: A case study of the Bluestocking letters ”. In: Nevala, Minna, Arja Nurmi and Minna Palander-Collin (eds.), The Language of Daily Life in England, 1450-1800. Sairio, Anni forthc. b. The Language and Letters of the Bluestocking Network. Submitted PhD. thesis. University of Helsinki. Schnorrenberg, Barbara Brandon (2004). “Montagu , Elizabeth (1718–1800)”. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. [accessed 20 July 2006]. Smith, L. Ripley (2002). “The social architecture of communicative compentence: a methodology for social-network research in sociolinguistics”. International Journal of Sociology of Language 153. 133–160. Strang, Barbara (1982). “Some aspects of the history of the BE+ING construction”. In: John Anderson (ed.), Language Form and Linguistic Variation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Tadmor, Naomi (2001). Family and Friends in Eighteenth-Century England. Household. Kinship, and Patronage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid, Terttu Nevalainen and Luisella Caon (eds.) (2000). Social Network Analysis and the History of English, Special issue of the European Journal of English Studies (EJES) 4 (3). Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (2003). “Lowth’s language”. In: Marina Dossena and Charles Jones (eds.), Insights into Late Modern English. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (2006). “Eighteenth-century prescriptivism and the norm of correctness”. In: Ans van Kemenade & Bettelou Los (eds.), Blackwell Handbook of the History of English. Oxford: Blackwell. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (2008). “The 1760s: the grammarians, the booksellers and the battle for the market”. In: Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), Grammars, Grammarians and Grammar Writing in Eighteenth-Century England. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (ed.) (2008). Grammars, Grammarians and Grammar Writing in Eighteenth-Century England. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Tinker, Chauncey Brewster (ed.) (1912). Dr. Johnson and Fanny Burney. London: Jonathan Cape. Accessed through University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/BurJohn.html. Valente, Thomas W. (1996). “Social network thresholds in the diffusion of innovations”. Social Networks 18. 69–89. Vickery, Amanda (1998). The Gentleman’s Daughter. Women’s Lives in Georgian England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Yáñez-Bouza, Nuria (2006). “Prescriptivism and preposition stranding in eighteenth-century prose”. Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics 6. http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/hsl_shl/ > Contents > Article Yáñez-Bouza, Nuria (2008). “Preposition stranding in eighteenth-century grammars by eighteenth-century grammarians: something to talk about”. In: Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), Grammars, Grammarians and Grammar Writing in Eighteenth-Century England. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Notes 1. This paper was first presented at the Social Network Analysis workshop, organised by the research project The Codifiers and the English Language at the University of Leiden, 29 May 2006.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||